Ukrainian-American Jews pray, anxiously await news from family back home

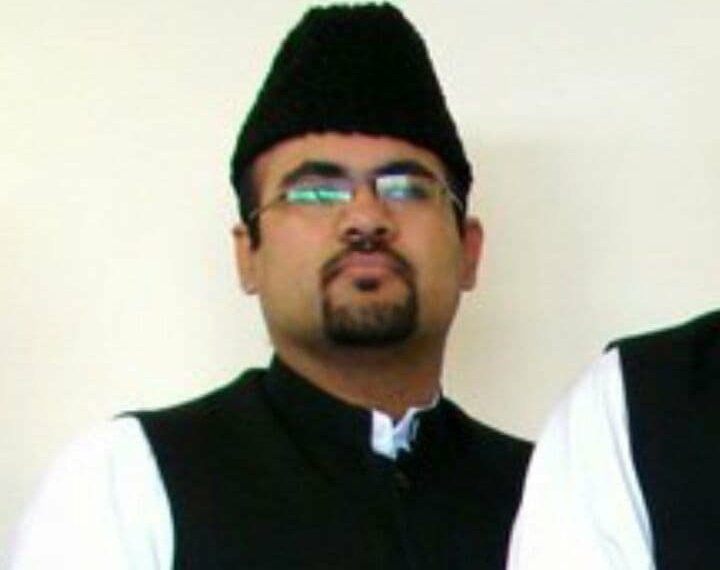

Following news of the Russian invasion of Ukraine has been scary in a personal way for Rabbi Menachem Shemtov and his wife Racheli. The latter grew up in Kyiv, where her father, Rabbi Jonathan Markovitch, is referred to as chief rabbi. Markovitch and his family had the opportunity to leave recently but chose to stay.

“They felt it was their duty to be there for their community,” said Shemtov, the director of Chabad Georgetown in Washington, D.C.

Shemtov, who has visited his in-laws on several occasions in more peaceful times, describes Kyiv as a “beautiful place, with a lovely Jewish community.” Markovitch has kept his synagogue, the Kyiv Jewish Center, open and is trying to stock as many necessities — flour, water, sleeping bags, mattresses and clothing — as possible. He has no way of knowing whether supply chains will hold or when the situation could deteriorate further.

“No one has any idea when any of that will happen,” Shemtov said.

Ukraine’s Jews — who make up some 0.2% of Ukraine’s population, according to the CIA World Factbook — do not feel especially vulnerable as Jews, according to Shemtov, but he notes history has taught Jews to be on high alert amid regional or global instability. His father-in-law’s community finds hope in its traditional faith and in gathering together in the synagogue, he said.

With the Jewish school and kindergarten closed for safety reasons, Shemtov said his young niece in Kyiv is enjoying sleepovers with friends at the synagogue, which helps distract her from what is happening outside the sanctuary’s walls.

In times of danger, Jews adopt a three-pronged response: “Torah, tefillah (prayer) and tzedakah (charity),” according to Shemtov. That means directing attentions to those in jeopardy while studying sacred texts, praying — particularly Psalm 130 and Psalm 20, both of which address danger — and donating to help those who are in need.

Praying in the “holy language of Hebrew” is always preferable, but one may do so in whatever tongue one knows best, according to Shemtov. “God speaks all languages,” he said.

Kyiv’s Jewish community requires tens of thousands of dollars to meet basic needs and stay as safe and comfortable as possible, said Shemtov, who directs those who want to help to the website careforkiev.com. So far, more than $51,000 has been raised, per the site, which reads: “This is a very serious situation and we are asking you to please do whatever you can to help.”

Nicole Krishtul, who works for the city of New York but spoke personally rather than professionally, is the first member of her family to be born in the United States. Her family comes from Mohyliv-Podilskyi — a small Ukrainian city near the Moldovan border — and her grandmother, whose non-Jewish neighbors hid her in their basement during the Holocaust, is from the Ukrainian village Ozaryntsi.

That grandmother’s descendants live in Ukraine, while Krishtul’s family moved to New York City in 1989 after her brother was born. In 2019, Krishtul and her family visited Mohyliv-Podilskyi, where her parents, who had not been back in two decades, were received very warmly, she said.

“It was one of the most emotional experiences I’ve ever had,” Krishtul said. “Within a few hours, it seemed like the whole city knew they came back.”

The driver who picked them up at the airport — a stranger — brought them food, figuring they would be hungry after their flight, and members of the small Jewish community insisted they join them for lunch at the synagogue.

Krishtul has witnessed many Ukrainian Jews in the United States worrying about friends and family back home, and a friend in Ukraine texted Krishtul’s mother at 1 o’clock in the morning alerting her that the war had started.

“I can’t wrap my head around the fact that Putin justifies his invasion as the ‘de-Nazification’ of Ukraine, which has a Jewish president who lost family during the Holocaust,” she said. “I highly doubt any Ukrainian Jew would have asked for this.”

Krishtul cautions those who want to help to beware of scams, which can surface during trying times to prey on the generous. American Jews can help by contacting federal elected officials and urging them to expedite accepting Ukrainian refugees, she said. They can also push for funds to provide housing, services and other kinds of support.

“In 1987, American Jews marched in Washington, D.C., to allow my family to come here,” she said. “I hope we can do the same again.”

Aaron Parnas, a lawyer in Miami, has an aunt, uncle and young niece living in Kyiv, while the rest of his family immigrated to the United States in the past 30 to 40 years. With reports that able-bodied men ages 18 to 60 cannot leave the country, Parnas said his uncle, 57, cannot leave. The three tried to flee the country before the invasion, but the roads were blocked.

“It would have been days of travel,” Parnas said.

Parnas is in touch with his family in Kyiv every day or two, as are other family members of his. His aunt, uncle and niece are safe, hunkering down at home, and they have what they need for now. “It’s scary, because they don’t know what’s to come,” he said.

Supply chains have been tenuous in Ukraine ever since Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, and the pandemic had already eroded them further, said Parnas, noting: “This will only exacerbate the issue.”

His relatives’ message for those who are following developments from abroad is not to trust Russian propaganda. Parnas’ aunt and uncle speak both Russian and Ukrainian. “Just because they speak Russian, they aren’t Russian. They are Ukrainian. They are proud to be Ukrainian,” he said.

He, too, advises the generous to be cautious about and to vet organizations purporting to help Ukrainians. With corruption in the country and near-continuous air strikes, he is skeptical that many can actually deliver direct aid now. His local Jewish federation in Miami has been collecting money and conducting a food drive, and he recommends that other American Jews who want to help be in touch with their local federations.

Amid everything, Parnas’ relatives in Kyiv are hopeful, and everyone is praying. “They just want this to be over,” he said.

Courtesy: RNS